WEEKEND THROWBACK

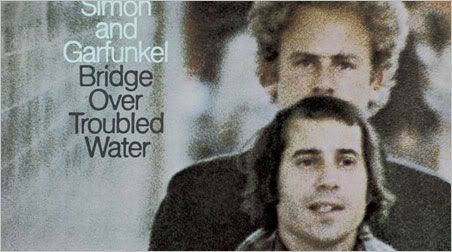

“Bridge Over Troubled Water”

from the album Bridge Over Troubled Water

1970

iTunes

Of the great ’60s folk-rock acts, Simon & Garfunkel seem to have endured the least, in terms of musical influence. Bridge Over Troubled Water far outsold anything put out that decade by the likes of The Byrds or Bob Dylan — but perhaps in this case who sold the most records to members of The Beatles is a more relevant figure.

Even in the ’60s, Simon & Garfunkel weren’t entirely easy to accept as critical figures. Although they were met with almost unanimous praise for their first few years of existence, by the time of the recording of Bridge Over Troubled Water they had come under attack. In Simon’s words, “It took two or three years for people to realize that we weren’t strange creatures that emerged from England but just two guys from Queens who used to sing rock ‘n roll. And maybe we weren’t real folkies at all! Maybe we weren’t even hippies!”

In fact, they used to sing rock ‘n roll professionally, under the moniker Tom and Jerry (hence the reference to Tom in “The Only Living Boy in New York”). Paul Simon, as has become exceedingly clear, had the kind of variety of influences and determined love of music for which Dylan was famous (and which he flaunted, flashing old Robert Johnson albums on the covers of his own). Although not their greatest album, it is perhaps Bridge Over Troubled Water where these manifold interests and influences are most apparent.

“Bridge Over Troubled Water,” the album’s first track, title track, and centerpiece, is a beautifully delicate gospel tune. Simon has related that he would listen to gospel stations on Sundays, when he couldn’t find any rock ‘n roll in the city. The vocal line on this track is stunning, and would carry power in any setting. In fact, the small, understated piano intro almost leads to the anticipation of a local gospel choir. In an album with this much attention to space, imaging, and texture, however, it explodes. By the fourth minute, when the orchestra has swollen and Garfunkel’s vocals have reached their limit of expression, the percussion is no longer drumming, but actual, literal bombing.

This combination of atmospheric textures with older, traditional American musical forms and lyrical concerns points directly, I think, to albums like Deserter’s Songs. While “indie” atmospheric pop is often supposed to derive directly from Brian Wilson’s ghost, their often non-standard instrumentation and sheer pretension of lyrical concern can be found almost wholly intact on this album, in this song.

The album’s other established classic, “The Boxer,” can’t live up to the experience of the title track. As others have said, it’s a traditional narrative song, lyrically. It follows much the same path as “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” opening with a solitary, rambling acoustic guitar and gradually piling on layers of orchestration and harmony. The song follows the fairly uninteresting story of a poor boy who suffers the slings and arrows of New York City life, ending in a hackneyed metaphor with a boxer who is wounded but fights on. One point that often seems missed is that Simon contrasts himself with the boxer here — he’s threatening to quit if the critics don’t leave him alone. Apparently, the repetition of the word “lie” here dozens of times is meaningless. If we’re to believe the author.

It’s perhaps when this album is supposedly “merely fun” that it’s at its best. Songs like “Keep the Customer Satisfied” and “Baby Driver” are irresistible, with the undefinable appeal of a square trying desperately to be hip. There is little that makes me happier than a drug dealer worrying about bad language while horns blare triumphantly, other than perhaps country songs about sex with the sound of cars going “vroom, vroom.” One would not imagine that Paul Simon was capable of sounding sleazy, but listen to the way his voice wraps around the heavy-handed innuendo of “engines” on “Baby Driver.” And “Cecilia” is the most “merely fun” of all. It’s these smoothest, poppiest moments that have lost the duo some credibility over the years — no matter what they’re doing, they sound too nice, too smooth. And, in turn, makes them easy to dismiss.

But it seems impossible to argue that Bridge Over Troubled Water isn’t a major artistic work. The awareness and completeness of the craft just won’t be denied. It seems hardly coincidental that such a subtly textured album would contain an ode of sorts to Frank Lloyd Wright, an architect whose main revolution came in the use of space. Space is what later Simon & Garfunkel relies on. They weren’t revolutionary in these techniques, of course — the already mentioned Spector and Wilson are only the most obvious of their predecessors — but they were the first to link it to the traditional American lyrical and musical forms which were so adept at conjuring their own spaces and universes even without modern technology. The potential here is astounding, and Simon & Garfunkel only just fall short of what they could have had.

One puzzling aspect of Bridge Over Troubled Water is the inclusion of “Bye, Bye Love.” Simon obviously had a respect for Spector, and loved this sort of rock ‘n roll — it is the live recording that makes it strange. By putting it on in this setting, they have denied it the importance and subtlety of Simon’s original work, which doesn’t seem like a goal that is compatible with the rest of the record. There is a distinct possibility that this is mere filler — by the album’s end, Simon is begging to play whatever will please his audience, but if so, it’s disappointing. With a few alterations, this could have been the major statement of the transition between the ’60s and ’70s. At is, it still contains some of its best songs and best times.